OVNI 2012

-

Programació (Pdf)

De l’oblit

Aquesta programació a tall d’assaig vol reflexionar sobre algunes de les realitats més preocupants del nostre temps, en concret l’experiència del conflicte amb el poder i la imminència d’un enfrontament encara major. Un conflicte que sobrepassa l’àmbit de la política per afectar la noció mateixa de civilització i l’origen del qual sembla emanar de la pròpia interioritat de l’ésser humà.

És així com plantegem, a través d’una sèrie de projeccions, una mirada més enllà de la immediatesa dels esdeveniments recents, de la lògica d’acció-reacció o de la persistent noció de l’altre com a negatiu. Per intentar guanyar una distància que permeti la reflexió.

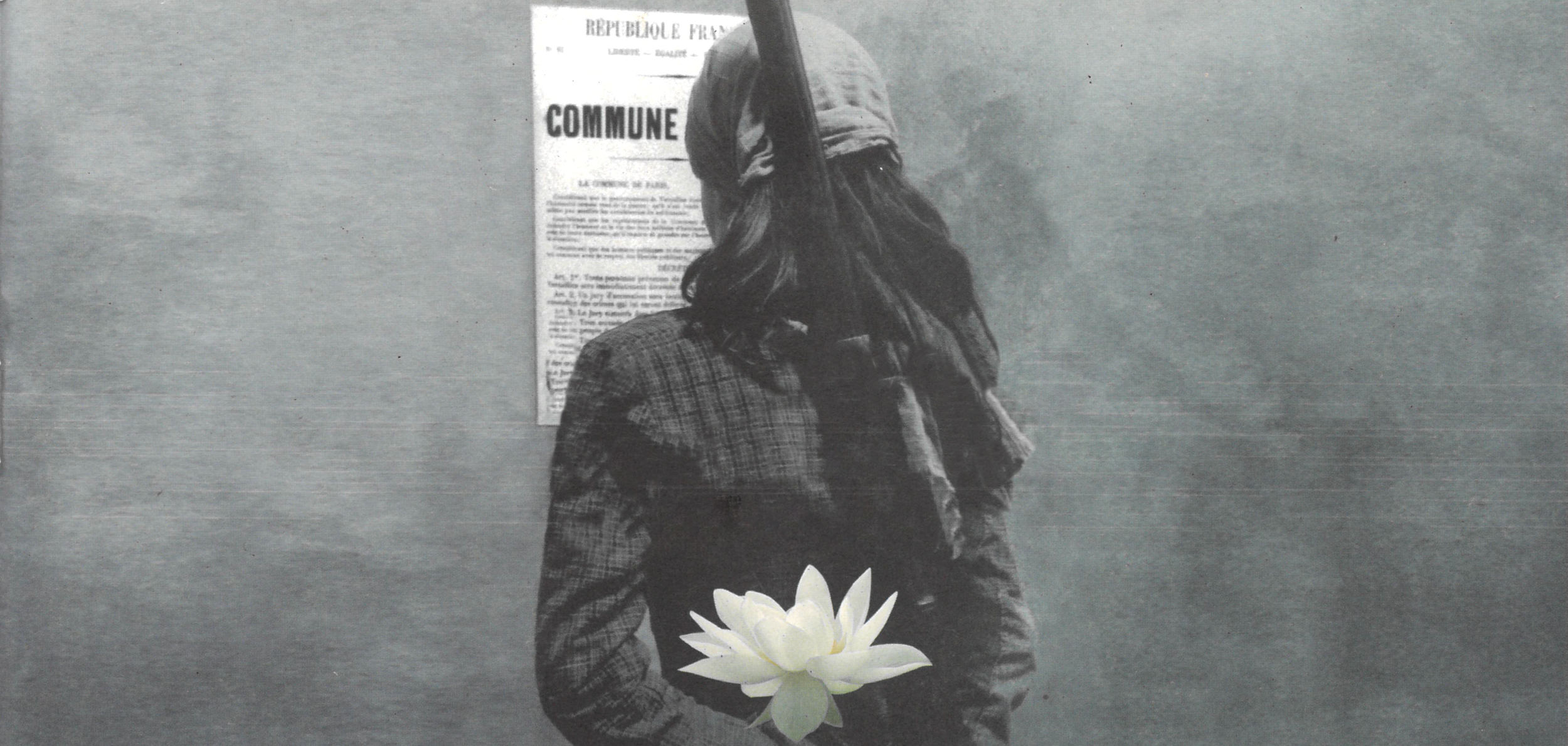

Aquesta mirada la proposem a través d’un doble nucli de la programació: La Commune, de Peter Watkins, i El Mahabharata, de Peter Brook. Contextualizats amb una sèrie de documentals i documents que reflecteixen la contemporaneïtat d’aquesta situació.

La Commune proposa una mirada al conflicte contemporani més enllà de l’oblit polític. Una reflexió des de la distància històrica sobre un esdeveniment clau com l’existència i extinció de la Comuna de París de 1871 i a la vegada un radical qüestionament de la realitat social dels nostres dies i de la seva representació mediàtica, ja que l’obra està interpretada per persones que exposen la seva situació actual al París de 1999. Projectem aquesta pel·lícula en 3 fragments. Cadascun d’ells anirà seguit d’un debat conduït pels integrants del col·lectiu Rebond La Commune, nascut a partir de l’experiència de realitzar aquest film.

El Mahabharata, de Peter Brook, proposa sobre el conflicte no ja una mirada històrica, sinó fora de la història, fora del temps lineal, per entrar en el temps mític del retorn constant, de la tensió dialèctica entre l’oblit i el record de la veritable naturalesa humana. Un conflicte que el Mahabharata presenta en diferents nivells, relacionats amb: la política (poder), la civilització, la supervivència de la vida sobre la Terra i simultàniament com a expressió de la batalla interior que es lliura en el si de cada ésser humà.

La projecció d’aquesta obra, en 3 parts, anirà precedida pels fragments d’una conversa amb Jean-Claude Carrière, guionista i adaptador teatral del Mahabharata de Brook, que vam gravar a París, a fi de tractar les claus d’aquesta obra en relació amb les nocions de conflicte i oblit.

Aquesta història tracta de tu

La programació s’inicia seguint el curs del Mahabharata, un immens poema que flueix com un gran riu, amb una “riquesa inesgotable que desafia qualsevol anàlisi estructural, temàtica, històrica o psicològica. Les seves portes s’obren constantment a altres portes que condueixen a altres portes. No és possible tancar-lo. Les capes de subtextos, de vegades contradictòries, en segueixen d’altres i s’entreteixen sense perdre el tema central. El tema és una amenaça: vivim en un temps de destrucció —tot apunta en la mateixa direcció—; podem evitar aquesta destrucció?(1)

Davant d’aquesta situació, el Mahabharata ens proposa, ja en les seves primeres línies, un viatge interior, un viatge de coneixement, de transformació.

- De què tracta el poema?.

- Tracta de tu. És la història de la teva raça, de com van néixer i de com van créixer els teus avantpassats i de com va esclatar una gran guerra. És la història poètica de la humanitat i, si l’escoltes amb atenció, al final seràs una persona diferent.(2)

La il·lusió del poder

Progressivament, el relat ens endinsa en l’enfrontament entre dos grups: els Pandava i els Kaurava. Un enfrontament que pren la forma d’un conflicte pel poder, però que neix d’una concepció quasi oposada de la vida. Amb tots els matisos i ambivalències, observem com els Pandava actuen tenint com a referència la cerca i el compliment del dharma, mentre que els Kaurava semblen guiar-se únicament pel desig i la por: desig de posseir el poder, por de perdre’l. Per això no s’estan d’utilitzar tots els mitjans, sense admetre cap mena de límit, mentre compten amb la complicitat dels seus pares: un rei cec i una reina que voluntàriament cobreix els seus ulls amb un vel.

Es juga llavors una partida de daus, una forma de representar i eludir momentàniament el conflicte directe i a la vegada un estratagema. La partida està trucada, el poder sempre fa trampa. El resultat només pot ser un: la derrota i la pèrdua de tots els béns, inclosa la llibertat. Endavant queda tan sols la l’exili i la guerra.

En els nostres dies, aquest joc trucat pren formes i noms que sovint emmascaren la seva finalitat: crear una realitat a mida dels interessos privats d’uns pocs. Com en el cas de l’anomenat lliure comerç, suposadament una partida justa en el joc de l’economia, però que per la desigualtat dels seus participants i la no-reciprocitat de les regles, entranya una voluntat de supremacia. Altres dissimulen una cosa tan evident com el caràcter corporatiu i empresarial d’algunes xarxes socials i de moltes eines virtuals que a penes si oculten el seu revers de control. Així, habitem una realitat de les aparences: aparentment escollim, aparentment ens comuniquem, aparentment estem fora de perill, gràcies a un espès entramat de dispositius socials. Però, inadvertidament cada dia, en complir el ritual de submissió que ha esdevingut el treball, el sistema educatiu, el sanitari, la cultura i l’oci, firmem un contracte silenciós:

Accepto la competitivitat com a base del nostre sistema, encara que sigui conscient que genera frustració i còlera en la immensa majoria de depredadors. Accepto que m’humiliïn i m’explotin a condició que em permetin humiliar i explotar a qui ocupa un lloc inferior en la piràmide social [...].Accepto que, en nom de la pau, la primera despesa dels estats sigui el de defensa […]. Accepto que se’m presentin notícies negatives i aterradores del món cada dia, perquè així pugui apreciar fins a quin punt la nostra situació és normal.(3)Òbviament, no firmar el contracte comporta diverses i creixents formes d’exclusió. Davant d’aquesta situació, la protesta es pot conduir sense problemes pels canals de l’aparença, renunciant a tota acció transformadora. Tot amb tot, si es vol fer real serà estigmatizada com a sectària, agressiva i violenta, amb independència dels mitjans i finalitats que esculli.

Del poder, el documental de Zaván, se centra precisament en aquest aspecte, el moment en què el poder mostra la seva vertadera naturalesa més enllà dels bells noms amb què vela i legitima el seu exercici. Aquest moment desvelat del poder es dóna quan recorre a la violència de la repressió. Gènova, 2001, centenars de milers de manifestants protesten als carrers. No és un fet aïllat, abans la protesta havia mostrat la seva força creixent a Seattle el 1999, a Praga el 2000 i comença a representar una possibilitat de canvi... Les autoritats blinden la ciutat, tanquen barris sencers, suspenen el tractat de Schengen per protegir la reunió dels vuit caps d’estat més poderosos. Segons fonts dels sindicats policials, es planteja deliberadament un escenari de violència extrema contra els manifestants, sense excloure la possibilitat d’alguna mort.(4) La violència policial es desferma, tothom és colpejat, comencen a caure els ferits, centenars, alguns en estat de coma, la situació deriva ràpidament en un parany per als manifestants, fins a constituir segons Amnistia Internacional “la major violació de drets humans de la història d’Itàlia des de la Segona Guerra Mundial”. Carlo Giuliani cau mort per dos trets al cap; posteriorment el comissari encausat va ser absolt. Aquesta mort, lluny de frenar la violència policial, sembla estimular-la i donar-li el seu vertader sentit, la repressió continua amb tota la seva força durant els dos dies següents. Del poder ens mostra aquest esdeveniment a partir d’un entramat de gravacions, en bona mesura material d’arxiu filmat pels mateixos activistes amb mitjans no professionals. La mirada que ens proposa és sovint una mirada silenciosa, imatges sense so, com observades a través d’una distància que paradoxalment apropa i permet veure-hi més enllà del vel de la imatge-notícia, deixant espai a l’equanimitat. Una equanimitat que, en lloc de suavitzar la denúncia, n’augmenta la gravetat. El que vam viure s’assemblava molt als mètodes de les dictadures sud-americanes dels anys setanta, recorda el diputat alemany Hans-Christian Ströbele.(5)

El 27 de maig de 2011, la policia va intentar desallotjar de la plaça Catalunya de Barcelona el campament de ciutadans que estaven exercint el seu dret de reunió en un espai públic. Es va produir, a la nostra ciutat, un dels episodis de brutalitat policial millor documentats de la història recent. També va ser històric per l’efectiva, exemplar i contundent resposta no-violenta dels manifestants. Els ciutadans agredits van presentar una denúncia per l’abús policial, però el jutge va decidir arxivar el procés sense ni tan sols escoltar els qui van presentar la querella. L’arxivament de la denúncia deixa en una gravíssima situació d’indefensió la totalitat de la ciutadania.

L’exili

Les formes d’exili són moltes, algunes ni tan sols comporten un desplaçament físic en l’espai, però sí la travessia d’un període del qual es desconeixen els veritables límits.

El Mahabharata ens planteja l’exili com un període d’extrema duresa, en el qual la mort està sempre present. I a la vegada la descoberta del seu revers: sortir de la parcel·la de poder que s’ostenta, ser desterrat de la ciutat per viure a la naturalesa representa, també, recuperar un contacte directe amb la vida, endinsar-se en la cerca del coneixement i del qüestionament radical de la realitat.

Un qüestionament que posa en joc la mateixa vida. Com en l’escena en la qual el dharma, sota la forma d’un llac, interroga els germans desterrats:

Què és més ràpid que el vent? El pensament.

Què podria cobrir la Terra? La foscor.

Dóna’m un exemple de desgràcia. La ignorància.

De verí. El desig.

Un exemple de derrota. La victòria.

Quin és el motiu del món? L’amor.

Què és el teu oposat? Jo mateix.

Què és la bogeria? El nostre camí oblidat.

I la revolta?, per què es revolten els homes? Per trobar la bellesa, sigui en la vida o en la mort.

I què és inevitable per a tots nosaltres? La felicitat.

I quina és la major meravella? Que cada dia la mort ens embat i vivim com si penséssim que som immortals.(6)

És la concepció dualista de la realitat, entre d’altres, la que aquí es posa en joc des de la seva mateixa arrel: l’oposat neix d’un mateix. És precisament d’aquest plec o tall del qual emergeix la noció o la il·lusió d’alteritat. Oblidar el seu origen és condició sine qua non per a l’exercici del poder: possessió, il·legalització i explotació de l’altre. Alteritat que atrapa fins i tot aquells que s’instal·len en el revers d’aquesta il·lusió.

No endinsar-se en el dualisme o bé recordar el seu origen implica també reconèixer l’ambivalència de tota experiència: la victòria és una forma de derrota, la realitat és real i irreal alhora...

Existeix també una ambivalència en la natura i en els moviments socials. A través de l’anàlisi de certs arbres i plantes que contenen tant elements productius com destructius, qüestionarem certes tendències polítiques que redueixen el discurs a una dicotomia entre el bé i el mal.(7)

El lament de la Terra

Però a la vegada, aquest joc manipulat del qual ens parlava el Mahabharata té també una lectura més enllà de l’enfrontament pel poder; una lectura més àmplia que ens planteja directament no el triomf d’uns sobre altres, sinó la supervivència de la humanitat i de la vida sobre la Terra.

He sentit el lament de la Terra. I què diu? Diu: Els homes s’han tornat arrogants, cada dia em produeixen noves ferides i són més i més nombrosos. Són violents, es deixen portar per pensaments de conquesta. Els homes imprudents em trepitgen. M’estremeixo i em pregunto: què faran, després? (8)

Aquesta violència sobre la natura no havia assolit mai una intensitat i extensió similar a la del capitalisme global, per al qual la natura és pura alteritat.

Solutions locales pour un désordre global, de Coline Serrau, se centra en un aspecte concret i decisiu d’aquesta violència: aquella que exerceix la —mai millor anomenada— agricultura d’explotació intensiva sobre la terra, sobre els agricultors, els productes i els seus consumidors. Ens recorda que el seu origen està estretament relacionat amb la tecnologia militar i sobretot amb una concepció de l’agricultura com a guerra i conquesta. Agricultors artesanals de diferents països (Ucraïna, França, el Marroc, Burkina Faso, l’Índia, el Brasil) ens parlen del caràcter femení de la terra i del seu treball, de la seva capacitat de generar comunitat i coneixement, enfront d’una concepció masclista que la veu únicament com una font d’explotació i profit a curt termini, com un simple suport físic per als productes químics de fertilització, herbicides, pesticides...

La terra queda com un camp d’experimentació genètica guiada únicament per la cerca del benefici immediat, en el qual la tecnologia juga un paper d’utopia sinistra capaç d’ocultar virtualment els cada cop més nombrosos deserts de terres empobrides o simplement enverinades.

I de nou en el rerefons hi trobem, com en el Mahabharata, la complicitat d’un rei cec i una reina que cobreix els seus ulls amb un vel. En aquest cas, la ceguesa i el partidisme d’uns governs dominats pels lligams de sang amb les grans multinacionals: centenars d’espècies vegetals, varietats de fruita, etc. són excloses dels catàlegs de llavors autoritzades, i el seu cultiu o comercialització esdevé il·legal, mentre que noves espècies transgèniques, l’impacte de les quals en el medi ambient i la salut a penes ha estat verificat, són ràpidament aprovades.

En un procés paral·lel al de la realitat política, el poder arriba a l’extrem d’il·legalitzar la realitat, amb la pretensió última de substituir-la. Una concepció que sembla emanar d’aquella visió d’Antonin Artaud que va escriure el 1947:

Cal reemplaçar, per tots els mitjans de l’activitat viable, la natura on sigui que pugui ser reemplaçada […] per assolir per fi el regne de tots els falsos productes fabricats, de tots els innobles succedanis sintètics, on la bella i legítima naturalesa no tindrà res a fer i haurà de cedir el seu lloc d’una vegada per totes i amb vergonya als triomfals productes de la substitució.(9)

Però el documental de Coline Serrau no vol aturar-se en el catastrofisme. Dóna la veu a pagesos, filòsofs i economistes que estan experimentant noves alternatives i denunciant les causes i les estratègies de l’actual crisi ecològica i política. Pierre Rabhi, Claude i Lydia Bourguignon, els treballadors sense terra del Brasil, Kokopelli i Vandana Shiva a l’Índia, el Sr. Antoniets a Ucraïna... Els diferents entrevistats demostren que hi ha opcions, que una alternativa és possible. Estan responent, amb elements concrets, als reptes ecològics i, en general, a la crisi de la civilització que actualment estem travessant.(10)

La guerra

En el silenci sepulcral de l’alba, a les 5 h 29 m 45 s la zona muntanyosa de la Jornada del Muerto va ser submergida en el gegantí flaix d’una llum intensa, que l’home només havia vist en les estrelles. Julius Robert Oppenheimer, l’anomenat pare de la bomba atòmica per la seva participació en el projecte Manhattan, escriu: Sabem que el món no tornarà mai més a ser el mateix; uns pocs van riure, altres van plorar, la majoria va romandre en silenci. Recordo aquestes línies del Baghavat Gita (Mahabharata) en què Vishnu diu: “Ara m’he convertit en la Mort, la destructora dels mons.”(11)

El 1965 Peter Watkins realitza The War Game (La Bombe), sobre els efectes d’un atac nuclear al Regne Unit. En veure el film els responsables de la BBC, que havia produït el film, queden horroritzats davant de la seva contundència realista i política. Watkins denuncia amb tota la cruesa el crim contra la humanitat que representa l’escalada nuclear i les irrisòries mesures de protecció amb què pretenen tranquil·litzar la població. Les dades procedents de les explosions atòmiques al Japó o dels bombardejos massius sobre Alemanya al final de la Segona Guerra Mundial donen una mesura, a petita escala, de la magnitud del desastre. En l’escenari immediat de l’explosió s’afegeix la tragèdia de la repressió i el control policial d’una població majoritàriament abandonada a la seva sort. La BBC, saltant-se tots els seus codis interns i després de consultar amb alts càrrecs del Govern britànic, decideix bloquejar durant 20 anys la seva emissió. Passa el mateix amb el seu següent film, una al·legoria política que denuncia la repressió política i policial als Estats Units durant el període Nixon. Punishment Park (1970) tot just dura 4 dies després de la seva estrena a Nova York, i mai més va arribar a emetre’s per televisió en aquest país.

Els seus següents treballs tornen a patir la marginalització mediàtica. La combinació d’un llenguatge cinematogràfic directe i innovador, la seva valentia i radicalitat en el tractament dels temes supera de bon tros el marge de tolerància de la indústria audiovisual. Finalment, el 1999 decideix realitzar —amb la producció del canal Arte— La Commune (París 1871). Watkins concep el seu rodatge i muntatge en oberta dissidència amb el que encertadament anomena la monoforma: una gramàtica que la indústria audiovisual cinematogràfica i televisiva imposada a tots els seus productes, justificant-la amb criteris suposadament objectius i tècnics: públic, visibilitat, programació... La monoforma no només predefineix el que el públic està capacitat per veure i els continguts que li interessen, sinó amb quina mena de mirada els ha de veure. Una mirada segrestada sota els efectes de la sobreestimulació visual, resultat d’un bombardeig ultraràpid d’imatges, efectes de so, veus, música, alternància frenètica de plans i moviments... La monoforma en totes varietats està basada en la convicció que el públic és immadur, que necessita formes previsibles de representació per “atrapar-lo”; és a dir, manipular-lo. Per això molts professionals se senten còmodes amb la monoforma: la seva velocitat, el seu muntatge impactant i l’escassetat de temps/espai garanteixen que els espectadors no puguin reflexionar sobre el que està succeint.(12)

El film La Commune representa una radical dissidència amb la monoforma. Opta pel blanc i negre, una durada propera a les 6 hores, un muntatge de plans llargs i pausats, absència de banda sonora, interpel·lacions directes a la càmera... El resultat, lluny de ser el monument fetitxista que canal Arte hagués acceptat sense cap problema, es converteix pel seu contingut, muntatge i vivència col·lectiva del rodatge en una experiència que qüestiona no només l’oblit històric, sinó el paper dels mateixos mitjans en la construcció de la realitat.

El rodatge de La Commune, en la nau d’una antiga fàbrica, involucra més de 200 persones. La majoria no són actors professionals, sinó ciutadans que accepten participar en aquest projecte sobre un esdeveniment històric del qual la majoria desconeix els detalls, i se situen en el film segons les seves preferències i afinitats polítiques, de tal manera que història (1871) i realitat contemporània (1999) estan en diàleg constant. El rodatge, per si sol, comporta una experiència revolucionària que afecta profundament molts dels que hi van participar. Durant aquesta experiència no només descobreixen una part oblidada de la seva pròpia història, que el sistema educatiu francès tracta dissimuladament, sinó que viuen la seva radical actualitat. Així veiem col·lectius de treballadors, dones, migrants i persones sense papers debatre sobre les seves condicions actuals de treball, sobre l’ensenyament, els mitjans de comunicació... alhora, interpreten la seva lluita a les barricades d’aquell París de 1871, on assisteixen atònits a la mort dels seus antecessors, la massacre oblidada de més de 40.000 persones.

Estem travessant un període fosc en la història de la humanitat, en què la combinació del cinisme postmodern (que elimina el pensament crític i humanista del sistema educatiu), la creixent avarícia generada per la societat de consum, la catàstrofe humana, econòmica i ecològica que es manifesta en forma de globalització, l’augment massiu del sofriment i l’explotació de la població de l’anomenat tercer món, i la conformitat i la normalització adormidores provocades per l’audiovisualització sistemàtica del planeta han format, de manera sinèrgica, un món en què l’ètica, la moral, la col·lectivitat humana i el compromís (amb tot el que no sigui oportunisme) es consideren “antiquats”. El malbaratament i l’explotació econòmica han esdevingut habituals, fins al punt que ho inculquem als nens. En un món com aquest, els esdeveniments de la primavera del 1871 a París representen (encara avui dia) la idea del compromís amb una lluita per un món millor i la necessitat d’algun tipus d’utopia social col·lectiva, tan necessària ara mateix com l’aire que respirem. D’aquí va sorgir la idea de fer una pel·lícula que mostrés aquest compromís.(13)

La Commune, lluny de l’èpica, obre també una reflexió sobre les dificultats de l’experiència revolucionària: el renaixement en el si de les velles estructures de poder o la tendència dels mitjans alternatius de reproduir els estàndards mediàtics, etc. Michel Foucault a L’esperit d’un món sense esperit, parafrasejant un manifestant, recorda que no n’hi ha prou amb un canvi polític ni econòmic, s’ha de produir un ensorrament de l’esquema de valors que ha construït aquesta a realitat i per damunt de tot hem de canviar nosaltres. La nostra manera de ser, de relacionar-nos amb els altres, amb les coses, amb la natura, amb l’eternitat, ha de canviar totalment. Només serà una revolució de debò si fem aquest canvi radical en la nostra experiència.(14)

Durant el 2011, de Tunísia a Toronto, del Caire a Barcelona, el món veu aparèixer l’emergència de moviments descentralitzats i autònoms de protesta. Si aquestes insurreccions populars ens ensenyen alguna cosa és que les revolucions no són esdeveniments aïllats, que conclouen amb el derrocament d’un govern o la presa del poder, sinó processos complexos que comparteixen objectius comuns. Així, veiem el fracàs de les barreres mediàtiques, policials i culturals que s’han construït entre els pobles. Totes aquestes protestes tenen alguna cosa en comú: el desig de llibertat i d’una vida digna, el rebuig a una desrealitat que ens oculta i segresta la vida.

Hores abans de morir, Dimitris va pagar el lloguer de l’apartament on vivia, sol. Després va agafar el metro fins a Sintagma i es va disparar un tret, amb una nota a la butxaca: Em dic Dimitris Christoulas, sóc un jubilat. No puc viure en aquestes condicions. Em nego a buscar menjar a les escombraries. Per això he decidit posar fi a la meva vida [...]. Crec que els joves sense futur algun dia prendran les armes i a la plaça Sintagma d’Atenes [la mateixa on va acabar amb la seva vida] penjaran tots els qui van trair aquest país. 4 d'abril de 2012.(16)

En el relat del Mahabharata, el camí de la guerra es fa inevitable quan els que ostenten el poder decideixen no concedir ni l’espai d’una agulla als desterrats. Quan les condicions per a la vida són negades, quan la il·lusió del poder posseeix i encega aquells que creuen ostentar-lo.

—S’ha fet tot el possible per evitar la guerra? Absolutament tot? Es pot evitar?

—Puc dir-te que no podràs escollir entre la pau i la guerra.

—Quina serà la meva elecció?

—Entre una guerra o una altra.

—Aquesta altra guerra, on tindrà lloc? En un camp de batalla o en el meu cor?

—No hi veig la diferència.(16)

No és casual recordar ara una vella història persa en la qual Peter Brook va basar un espectacle.(17) 30 ocells escolten un dia parlar del Simurgh, per a uns aquesta misteriosa paraula significa el Poder mateix, per a altres és el sentit oblidat de la Veritat, no ho saben exactament... però s’hi senten irresistiblement atrets, com en la foscor les papallones nocturnes ho són per la llum d’una espelma. Així que decideixen iniciar aquest llarg i difícil viatge a través de la foscor sense durada precisa, ple de perills i encontres, en què travessen les valls del dubte i de l’amor, de la separació, l’astorament i la mort... per descobrir al final d’aquest camí que Simurgh són ells mateixos (Simurgh en persa significa 30 ocells).

abu ali

Notes:

De l’oblit, i el que aquesta paraula evoca, ha estat possible gràcies a la inspiració de Jean-Claude Carrière. Igualment hem d’agrair molt especialment la col·laboració i les idees de Patrick Watkins i de Toni Cots.

(1) The Great History of Mankind, Jean-Claude Carrière, 1989.

(2) El Mahabharata, en versió de Peter Brook i Jean-Claude Carrière, 1989.

(3) Le Contrat, Anònim a la Xarxa, 2003.

(4) El atropello de Génova, Rafael Poch, 2012.

(5) Ibídem.

(6) Vegeu nota 2.

(7) Íd.

(8) Vegeu nota 2.

(9) Solutions locales pour un désordre global, Coline Serreau, França, 2009.

(10) Julius Robert Oppenheimer:

(11) Peter Watkins: http://blogs.macba.cat/peterwatkins.

(12) Peter Watkins: http://pwatkins.mnsi.net/commune.htm.

(13) Peter Watkins: http://blogs.macba.cat/peterwatkins.

(14) L'esprit d'un monde sans esprit, Michel Foucault, 1979.

(15) Podeu llegir la nota íntegra de Dimitris Christoulas, de 4 d’abril de 2012, a:

(16) Vegeu nota 2.

(17) Mantiq al Tayr [El llenguatge dels ocells o la conferència

dels ocells], Farid Uddin Attar, Pèrsia, segle XI.

(18) Mantiq al Tayr, El Lenguaje de los pájaros o La conferencia

de los pájaros Farid-ud din Attar, Persia S XI.

Centre de Cultura Contemporània de Barcelona

Montalegre 5. 08001 Barcelona

+34 93 3064100

Imatge: La commune. Corina Paltrinieri