/ ANTIMILITARISME! /

Karl Liebknecht

(Leipzig, 1871 - Berlín, 1919)

-

(Fragment)

La guerra actual –és a dir, la guerra imposada per l'imperialisme plenament desenvolupat– mostra més que qualsevol altra guerra, que l'estratègia militar és un assumpte que concerneix no solament a l'exèrcit, sinó a tot l'Estat, a tota la vida econòmica i a tota la població, el caràcter i la capacitat d'acció de la qual influencien fins al més alt grau, fins i tot en temps de pau i amb tota evidència a l'organització de l'exèrcit. Igualment que tota la vida econòmica es transforma en funció del militarisme, l'Estat s'ha convertit en una màquina perfeccionada fins i tot en els menors detalls, molt més "completa", potent i complexa que la màquina espartana, tan admirada, que al costat d'aquella, produeix l'efecte d'una javelina grega comparada a un obús del 42 de les fàbriques Skoda. La burocràcia s'ha elevat al nivell d'una "misilocracia". Des de la direcció tècnica oficial, semioficial i privada destinada a enfervorir a l'opinió pública en favor de la guerra; des de la mobilització de l'exèrcit, dels transports i del servei d'informació; des de la mobilització financera i la regulació de la producció per satisfer les necessitats de l'exèrcit (armes i municions, equip i vestuari, material sanitari, etc.) fins al condicionament continu de la població civil (censura de "l'opinió pública", declaració de l'estat de setge, persecució d'aquells que s'oposen a la guerra, compreses les famílies dels soldats), l'administració de l'Estat sota la protecció de la dictadura militar és un camp d'activitat extraordinari. Si els parlaments ajuden a l'administració de l'Estat en aquesta acció, això significa que els parlamentaris de les classes dirigents donen a l'Estat un suport important en el seu propi interès.

La vida econòmica assegura les necessitats de l'exèrcit. Tant com el material humà, el material econòmic necessari per a la prossecució de la guerra no és avui, contràriament a temps passats, una magnitud fixa donada d'una vegada per sempre, sinó un producte social que es renova sense parar i alhora canviant, tant pel que fa a la quantitat com al gènere, segons les necessitats del moment. Donades la diversitat i la immensitat de les necessitats corrents de l'exèrcit, la part de la vida econòmica consagrada a satisfer-les és absolutament impossible d'avaluar. La noció "indústria d'armaments" i fins i tot "indústria de guerra", així com la "d'òrgans de distribució" posats al seu servei són extraordinàriament àmplies. De la mateixa manera, la fabricació i distribució dels productes destinats a la població civil, compresos els que serveixen per a satisfer les necessitats intel·lectuals (panen et circenses) formen part de les necessitats de la guerra moderna. Cal sostenir la moral de la població civil com a reserva de l'exèrcit.

La sustentació de la "moral", de "l'esperit" forma part de les necessitats absolutes de la guerra moderna. Així, situada fora de l'exèrcit i encarregada d'aprovisionar-lo, una gran part de la població forma part dels instruments humans del militarisme imperialista.

El militarisme sempre està en guàrdia quant a la moral de la població en conjunt, dels cercles d'interès d'aquesta i dels seus grups ideològics; sempre està al corrent de tot símptoma relatiu a la moral que es manifesta en queixes i protestes de tota mena.L'estat d'ànim dels soldats i de la població civil, en temps de guerra, constitueix un fenomen singular. Sobretot al front, en estat de perill permanent, amb una intensa tensió nerviosa, aquest estat d'ànim és angoixant, monomaníac, primitiu; els impulsos dominen, la raó emmudeix; la visió general es perd, fins i tot pel que fa als esdeveniments diaris del conflicte mateix; tot pensament que pugui anar més enllà de la defensa pròpia desapareix completament, fins i tot la preocupació per l'ajuda; els companys. Esmussar, atordir, impedir que el soldat sigui amo de si mateix, que pensi amb claredat és un mètode excel·lent de dic moral i de mecanització per aconseguir una docilitat completa. Però aquest mètode també troba el seu límit. En cas de guerra prolongada, fins i tot la perspectiva del triomf desapareix i la impulsivitat de la vida moral del soldat es transforma fàcilment en un perill creixent.

Així, doncs, el militarisme està situat, en la lluita contra el perill interior en temps de guerra, davant dificultats més greus que en temps de pau.

No fer res que pugui enfortir aquest esperit en l'exèrcit i en la població civil és la primera obligació de la lluita de classe contra la guerra abans i després que aquesta esclati.

Davant els horrors de la guerra moderna empal·lideixen els perills de la més furiosa dictadura militar. El postulat del rei-soldat, segons el qual el soldat ha de tenir més por als seus superiors que a l'enemic, no pot, donada la crueltat infernal dels mètodes de guerra moderns, ser mantingut: l'arrel de la disciplina militar forçada es podreix.

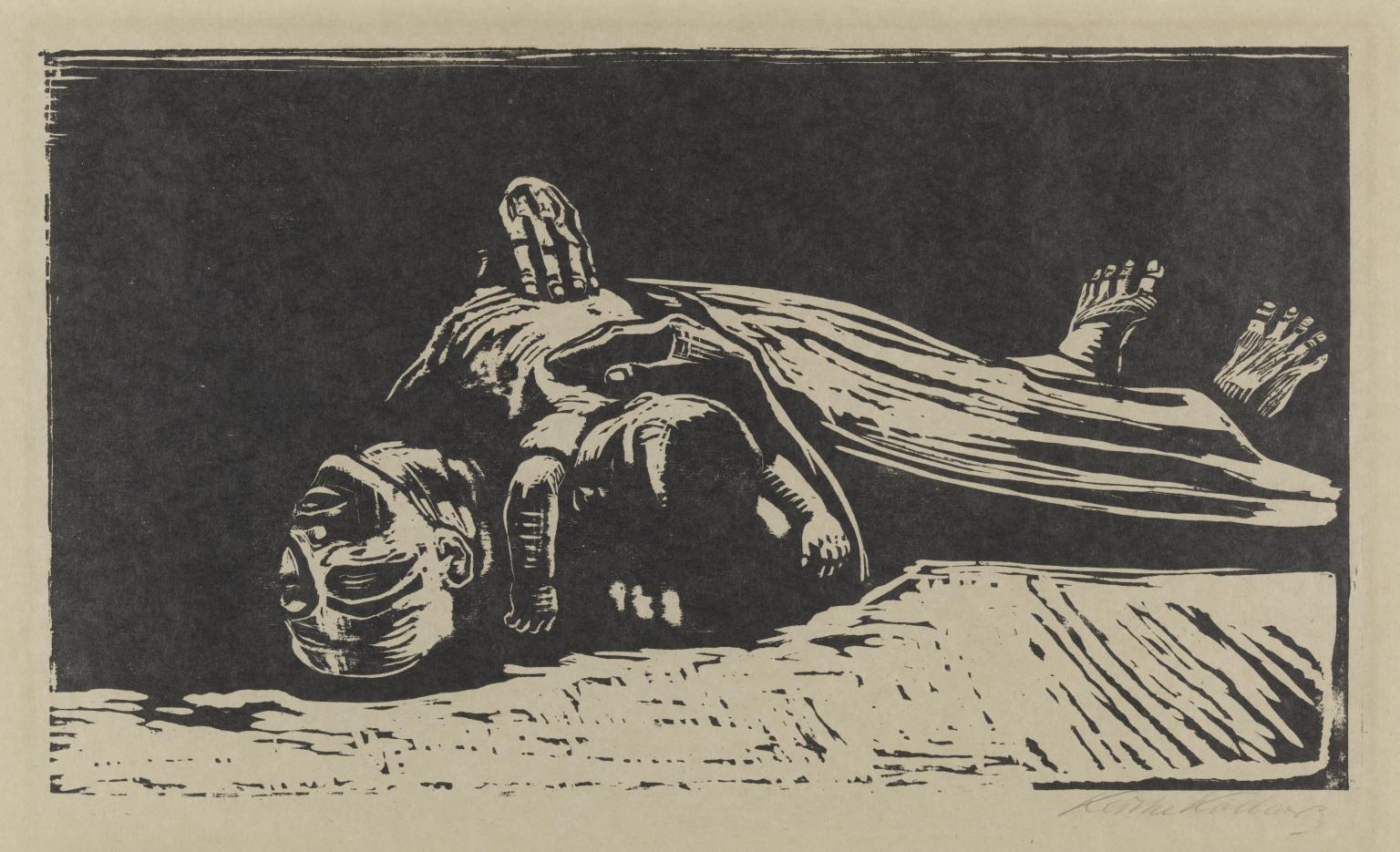

La massa del poble ha de lluitar per imposar per si mateixa el seu objectiu d'acabar amb la guerra en lloc de sacrificar-se pels de l'enemic, que encara són els amos; ha de rebutjar l'esperit de sacrifici servil.Gravat de Käthe Kollwitz