/ LA MIRADA DE L' ÀNGEL /

-

Curcio Malaparte va parlar dels àngels en el seu llibre Kaputt. Quan va recórrer el gueto de Varsòvia escortat per un membre de les SS, va poder apreciar com el port atlètic de l'ari, el seu rostre bell, la seva mirada clara i altiva contrastaven amb la massa fosca de jueus famèlics i moribunds que s'apartaven al seu pas. "Em sentia com si caminés al costat de l'àngel d'Israel", va escriure.

Un dron sobrevola un barri destrossat per les bombes. La precisió de la màquina permet apreciar la magnitud de la devastació. Els míssils han derrocat desenes d'edificis. Uns altres no són més que esquelets de ferros retorçats i maons calcinats. El silenci i la quietud emboliquen l'escena filmada sota un cel afable. El barri és ara una enorme fossa comuna. Però el dron, amb el seu llarg travelling, el converteix en una altra cosa, imprimeix a l'escena un to estrany. La banda sonora amb la qual el realitzador ha buscat emfatitzar el dramatisme del moment acaba subsumint la seqüència documental als codis de la ficció. L'agilitat única del dron, la seva ingravitació harmoniosa, és la d'un àngel que observa la destrucció i el sofriment des de la seva impunitat celestial.

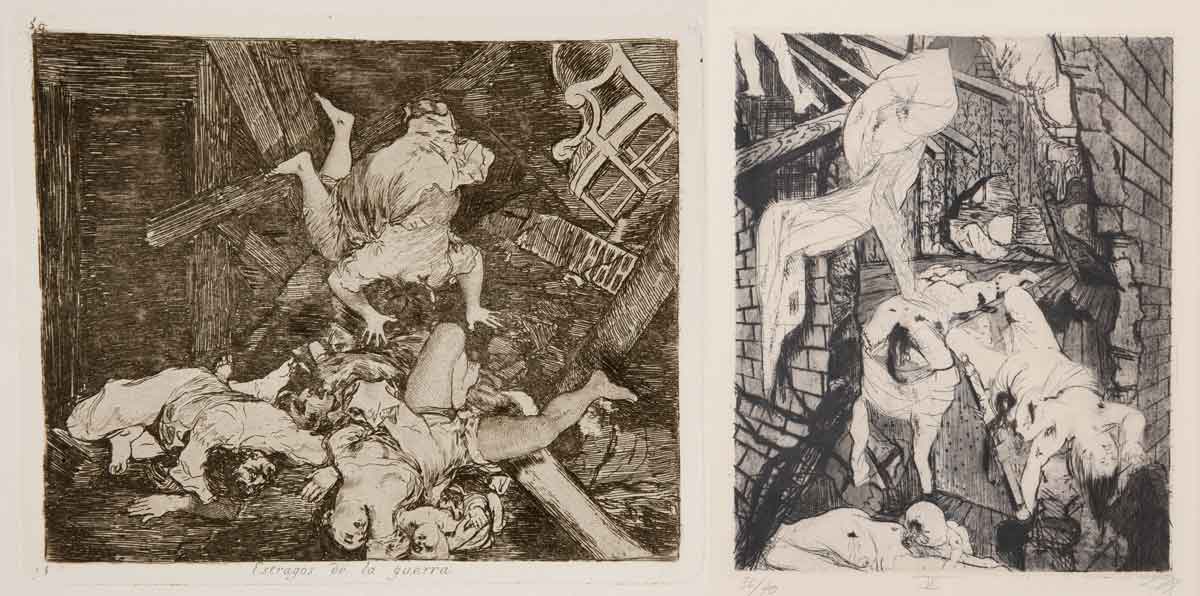

Tal vegada per això, per a evitar qualsevol indici de misticisme falsificador, Otto Dix va encarar els efectes del bombardeig ran de terra. El seu gravat segueix fil per randa un altre gravat de Goya. En totes dues obres, les víctimes és desmadeixen entre els enderrocs. Cauen cap avall i és des de baix des d'on tots dos pintors ens obliguen a mirar-les. La visió aèria de l'àngel victoriós no té cabuda aquí. La glòria de l'exterminador es consolida en la ignomínia dels vençuts. La denúncia de l'horror només es pot fer des de l'infern.

Font:

https://www.youtube.com/