/ PAMFLET I REVOLUCIÓ /

-

A diferència del comunicat, que tendeix a encasquetar-se en l'aspecte jurídic, el pamflet funda el seu poder en la seva capacitat explosiva. La concisió feridora que el torna tan efectiu és també la que el situa inevitablement a les fronteres del que és demagògic. Però aquest és un risc que assumeix amb naturalitat. La mirada assossegada i displicent de l'acadèmic no té lloc aquí. Les lluites de les quals aflora el pamflet no han sortit dels caps dels doctes sinó de la tensió nerviosa dels conjurats. Primer ha estat un exabrupte retolat a la porta el vàter, després unes paraules gargotejades en un mur sense fanal, una pancarta escrita a brotxa sobre una tela improvisada. Finalment, el fullet que incendiarà els carrers. Tosc, indiferent a la gramàtica, amb la tinta mig esborrada per la pluja, altiu en la seva arrogància enfront d'això que anomenen "estratègia".

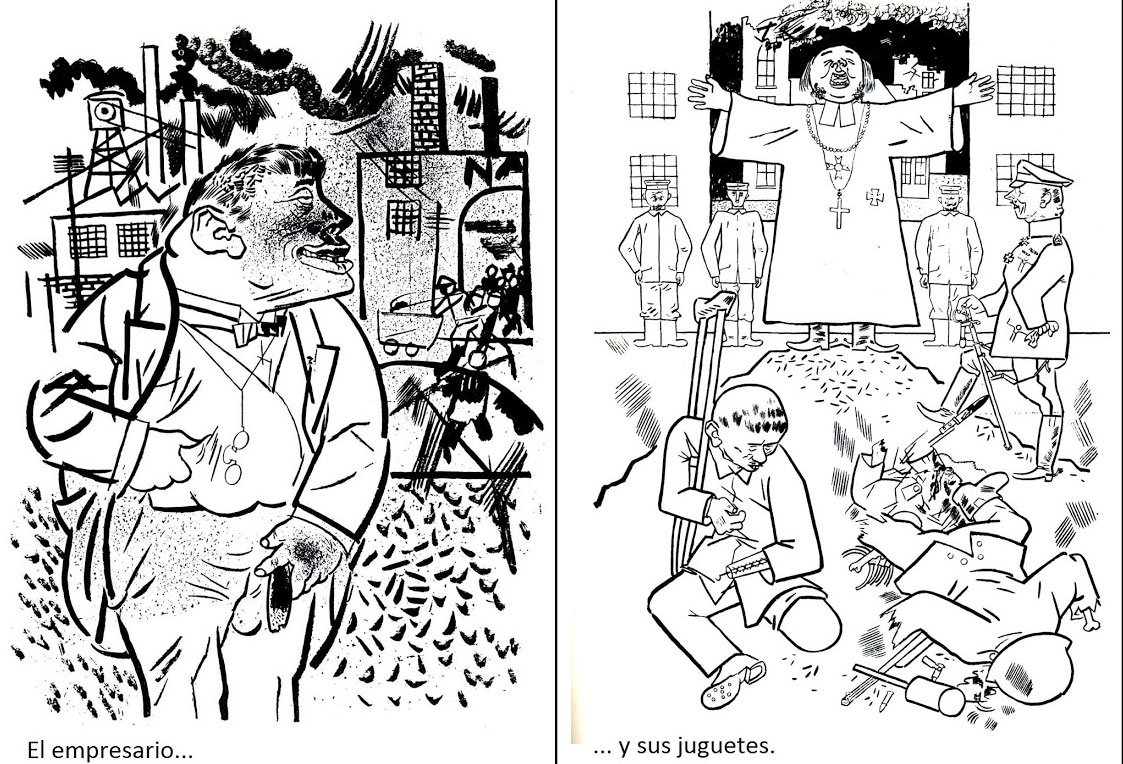

George Grosz va triar el pamflet per a realitzar els seus gravats contra la guerra. La imperfecció i la immediatesa esmolaven aquests traços durs, rabiosos, intencionadament allunyats de la pulcritud dels clàssics. La seva obra era també una escopinyada sobre els pintors de cavallet com Paul Cezanne o Henri Rousseau, als quals considerava uns necis embriagats de santa ingenuïtat. Com ficar Grosz al Museu? El problema no es pot solucionar fent prestidigitació amb els termes lingüístics. Quan els encarregats de les exposicions es deien "comissaris", la cosa tenia un cert sentit. Perquè el lloc natural per mostrar els pamflets no eren els museus, sinó les comissaries. I com els comissaris artístics respectaven la labor dels comissaris policials, que atresoraven amb zel els pamflets confiscats en les seves batudes, aquests mai els traslladaven de la comissaria al museu, tret que fos com a art degenerat. En canvi, trasbalsa. Ficar a Heidegger en el terreny dels comissaris ha convertit l'exposició dels pamflets revolucionaris en alguna cosa així com l'exhibició de la pell dissecada dels vaguistes. L'art momificat ha substituït a l'art degenerat.

Ideat com a obra d'un dia, editat en impremtes ocultes en pisos clandestins, sembrat de taques de tinta a causa de la poca qualitat del paper, el pamflet viu en les butxaques dels transeünts. I, no obstant això, molts d'ells conserven activa la seva càrrega durant anys, com aquestes bombes que de tant en tant apareixen en els vells camps de batalla i esclaten quan un menys li ho espera. Vint, trenta, tal vegada cent anys després, apareix un pamflet entre les fulles d'un llibre que venien a preu de saldo als Encants. Qui ho va amagar allí? El sorprès lector el desplega amb delicadesa i torna a llegir-lo, i, durant uns instants, sent l'alè dur d'una lluita sense concessions. Entén així, de la forma més simple i directa, que no hi ha obra literària que pugui competir amb aquest tros de paper groguenc.

Solia escriure amb el seu dit gran en l'aire:

«¡Viban los compañeros! Pedro Rojas»César Vallejo